First came a pandemic. Then two years of floods.

Now, a belch of hot air from President Donald Trump is the latest disaster to plague Vermont businesses that have long courted Canadian customers.

Trump’s spasmodic, he-must-be-joking comments about turning Canada into the “51st state,” coupled with his maybe-he’s-serious tariffs on the country’s imports, have unleashed fury in the north. Many Canadians have vowed to boycott U.S. goods and not to venture south, pushing cross-border trips nationwide to lows not seen since pandemic lockdowns.

Vermont’s tourism economy finds itself caught in this peculiar political tempest. The state has close business and social ties with Québec, and Canadians — mostly Québécois — make up a significant segment of visitors here. They contribute roughly $150 million to the $4 billion tourist economy, according to state estimates, the bulk of which supports border regions, especially the Northeast Kingdom, as well as cities such as Burlington.

Businesses in northern Vermont are bracing for a summer with fewer Québec license plates in their parking lots. They’re already taking calls and emails from loyal guests expressing their regrets or cancellations. Web traffic from Canada and web sales to Canadian customers are down. For those Canadians who are interested in visiting Vermont this summer, the low exchange rate for the Canadian dollar makes travel to the U.S. more expensive — a powerful disincentive.

Cross-border travel into Vermont has been lagging since February, when Trump’s rhetoric and trade policy began souring relations with Canada. The trend continued in April, according to data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection: Just 98,000 travelers crossed into Vermont from Canada last month by car, down from 147,000 in April 2024 and not many more than the 84,000 who came in April 2022, when cross-border travel was just resuming following the pandemic lockdown.

With tens of millions of dollars in tourism revenue at stake, some businesses are searching for ways to entice Canadian visitors with financial deals or personal appeals. Those with advertising budgets are pivoting to new domestic markets rather than trying to persuade a reluctant clientele. State leaders, meanwhile, are promoting the close ties between neighbors in an effort to distance the Vermont brand from a toxic national one.

Most are being careful in their overtures to Canadians, lest their attempts at courtship be received as insensitive to their customers’ anger at the president.

“We’re definitely ready to welcome them back,” said Jenifer Oliphant, general manager of the Wildflower Inn, Restaurant & Pub in Lyndonville, “whenever they’re ready to come.”

Canadian guests account for about 10 percent of overnight bookings at Oliphant’s business, located adjacent to the Kingdom Trails network that is popular with Canadian mountain bikers. They comprise a larger proportion of its dining clientele. Inn cancellations started coming in a couple of months ago, Oliphant said. Some Québécois who are still making the trek have told Oliphant, to her surprise, that they were nervous that Americans wouldn’t receive them warmly.

“When we see someone that pulls up in a car from Québec,” she said, “I make a point to go over and tell them, ‘Thank you for coming.'”

Wildflower typically advertises to Canadians through social media. But Oliphant pulled those ads last month because they were attracting angry, profanity-laced comments. “I think everything was so raw,” she said.

Instead, the inn is experimenting with ads targeting domestic markets outside New England in hopes of offsetting the drop in Canadian visitors this summer. Wildflower’s lodging revenue has increased in recent years, and Oliphant thinks it can weather the Canadian boycotts. As for the restaurant, “that’s still to be seen,” she said.

About 500,000 Canadians visited Vermont in 2023, out of nearly 16 million total tourist visits, according to a report commissioned by the Vermont Department of Tourism and Marketing. Visitation has been slow to recover from the pandemic, before which Canadian tourists numbered 700,000. Still, they’re a summer fixture around Lake Champlain, downtown Burlington, and at general stores and diners in the Northeast Kingdom.

“You can’t go through the grocery store in the summer and not bump into 10 people speaking French,” said Loralee Tester, executive director of the NEK Chamber of Commerce.

Certain destination vacation spots are expecting only modest declines. Jay Peak, which counts on Canadians for half of its revenue, has experienced just a “single-digit” drop in its early-bird ski season pass sales, president and general manager Steve Wright said. The resort has long offered “at par” pricing for Canadians, which allows them to buy passes at a one-to-one exchange rate. The deal has taken on greater importance this spring because the Canadian dollar is especially weak, worth just 72 cents as of May 20.

Purchases by Canadians were down nearly 80 percent at one point, Wright said. He personally called several dozen longtime Canadian pass holders to assess how they were feeling. The conversations helped him appreciate the degree to which ordinary Canadians were angered by Trump’s rhetoric even more than his policies.

“It’s galvanized a lot of that country in a way that nothing else would,” Wright said.

The calls convinced Wright that Vermont should continue marketing its special relationship to Canadians.

But few Vermont businesses have as close a relationship to their Canadian customers as Jay Peak does with its winter passholders. Emma Arian, executive director of the Vermont Brewers Association, counts on Québécois for 500 or so guests at its 6,000-capacity brewers festival, scheduled for July 18 and 19 on the Burlington waterfront.

Inspired by Jay Peak, the association is offering at-par pricing for Canadians for the first time this summer. It also made a point to attract a trio of breweries from Québec to participate in the 32nd annual event. Organizers are planning to promote the event during an upcoming Vermont Green FC home soccer match against a team from Québec.

The association knows that Canadian visitors are important consumers for the state’s craft brewing industry, and they are hoping at-par pricing and other small gestures at the festival will help maintain that support.

But Arian is trying not to be “too pushy about it” by respecting the decisions of otherwise loyal attendees who have said they plan to stay home this year.

Indeed, it’s unclear how many Canadians might respond to such enticements. Gwyneth Edwards, an associate professor at the graduate business school HEC Montréal who teaches international strategy and cross-cultural management, said her family has put several trips to the United States “on hold” for the time being. She knows many friends who have canceled their trips, though some students have told her they’re still interested in visiting.

Edwards believes Trump’s approach to trade is “ridiculous” and said it reflects “his belief that he is an all-powerful president who can dictate to the world how the economy will run.”

She maintains a stronger affinity toward Vermont but doubts that special offers or expressions of support can convince her and others to visit.

“I am not sure that is enough to overcome the impact of Trump’s decisions,” she said.

Alain Saulnier, a journalist and former head of Radio Canada’s French-language programming, organized an anti-Trump rally in Montréal last month that drew 4,000 attendees.

“With all the respect I have for the people of the United States, you have to respect what the Canadians did to maintain a different way of life,” Saulnier said, adding that his English is limited.

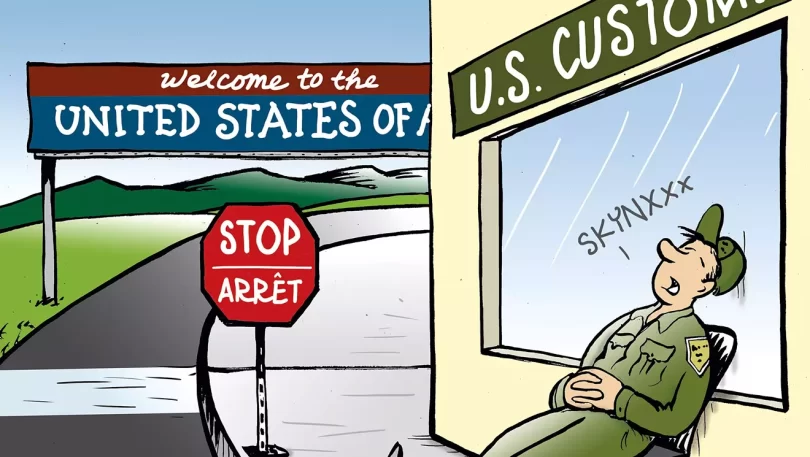

Saulnier noted that many Québécois feel trepidation about crossing the border. The Université de Montréal has encouraged people to leave behind their phones and computers when visiting the U.S., to protect themselves from U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents’ prying eyes. Saulnier himself assumes he’s on a government blacklist due to his public comments about Trump and his administration. He doesn’t plan to visit as long as Trump is in power.

Vermonters’ own demonstrations against Trump and the Elon Musk-helmed Department of Government Efficiency have been reassuring, Saulnier said, but he remains committed to boycotting the country on principle.

A contingent of Vermont activists traveled to Montréal earlier this month in a symbolic show of solidarity. The activists made at-par purchases at the Jean-Talon Market, forgoing the exchange-rate discount they would otherwise enjoy. The event, which featured speakers, attracted a flurry of news coverage in the Canadian press. Vermont State Treasurer Mike Pieciak and Burlington Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak joined the group. Pieciak bought Canadian maple syrup, he said.

The trip was organized by East Montpelier resident Miriam Hansen, who was born in Montréal but has lived in Vermont for much of her life and worked at the Haskell Free Library and Opera House in Derby Line that straddles the international border.

Hansen said the purpose was to show solidarity with Canadians, not to encourage them to reciprocate by vacationing in Vermont.

“We need to make common cause. We need to understand each other,” Hansen said. “Yes, the Canadians need to boycott us. There needs to be suffering on both sides.”

That’s bitter advice for Hill Farmstead, the legendary brewery in Greensboro Bend that gets more than one-quarter of its customers from Canada.

Visitation dropped almost immediately following Trump’s “sabre-rattling” in February and March, according to Bob Montgomery, the brewery’s director of brand quality. Online pre-purchases are down more than 20 percent, he said, and he’s received “polite” emails from longtime Canadian customers who are skipping annual traditions this summer, such as an upcoming dandelion-picking event.

Another hurdle: Retaliatory tariffs enacted by the Canadian government require day-trippers from Québec to pay a 25 percent surcharge on Hill Farmstead brews they bring home, which they must pay at the border upon their return. Due to American tariffs, the brewery is incurring higher costs for the glass bottles and growlers it sources from Québec.

Altogether, the situation is putting a damper on Hill Farmstead’s 15th anniversary celebrations. Montgomery has been planning an especially large series of parties, in part because COVID-19 crashed Hill Farmstead’s 10th birthday. In the interim, the brewery endured the economic fallout from a pair of July floods.

Montgomery, who lives in Derby and has family ties to Sherbrooke, Québec, said he is beyond frustrated at the hit the business is poised to take again this summer.

“This administration’s nonsense has really poisoned what has always been a pretty spectacular relationship,” he said. “It will take years to rebuild what has been damaged in such a short period of time.”